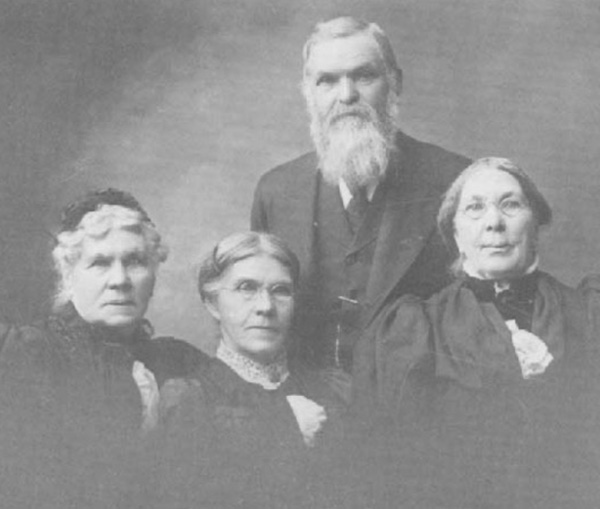

PHOTO BY: CHRIS EMEOTT

Playing goalie was 70-year-old Kim Newman’s entree to the world.

Longtime Woodbury resident Kim Newman undoubtedly qualifies as one of the oldest goaltenders in the State of Hockey.

The 70-year old Newman started playing hockey at age “5 or 6” in his native Eveleth, Minn., which has a storied history in the sport, dating back longer than he has been alive.

Newman didn’t pick the position, which can be a high-pressure spot when a team’s fortunes depend on the netminder’s ability to keep opponents from scoring. He wanted to join a fourth-grade hockey team and, “fortunately or unfortunately, the only position left was goalie.”

In the era when most kids’ hockey games were played outdoors, goalies got colder than anyone else on the team. But Newman got to play many games in the Eveleth Hippodrome—one of the earliest indoor arenas in Minnesota—and learned to enjoy the challenge of being the team’s last line of defense.

In the early decades of hockey, goalies didn’t wear face protection, and stitches were an accepted part of playing the position. Newman didn’t get his first goalie mask until playing in bantams, sometime around eighth grade. The Eveleth High School varsity goalie had been the first in town to get one. Newman’s first mask was hand-crafted by his coach, who lived across the alley.

The process started with covering his face with Vaseline, then covering it with plaster of Paris to make a mold. Then the coach built the form-fitting mask out of fiberglass strips.

Playing in the goal for his high school team, “I tried not to make it a habit, but I would get hit in the mask a few times a year. Every time I got hit, the mask concentrated the blow right on the bridge of the nose. It made my eyes water but it kept me from getting cut,” Newman recalls. One time, his mask was shattered by a stick, necessitating a few stitches in his lip. But, over the years, he’s managed to avoid face-hits; “I’ve either been good or lucky.”

The Eveleth high school team played most of its games indoors, but Newman remembers playing two outdoor games, versus Iron Range rivals.

After three years of varsity play and making all-Iron Range Conference in his senior year, Newman accepted an appointment to play at the Air Force Academy in Colorado, which was just starting a varsity hockey program. (Newman’s high school coach, John Matchefts, coached the Air Force team from 1972 to 1986.)

To get the necessary Air Force appointment as a warrant officer—the category athletes were placed in—Newman obtained the necessary nomination from then-U.S. Senator Walter Mondale. As a fledgling college program, “we weren’t very good at first,” he recalls. “Then, my junior and senior year we got pretty good and were able to beat [Western Collegiate Hockey Association teams] Colorado College and Notre Dame.”

After graduating in 1971 with a degree in engineering management, Newman got a chance to travel internationally as a member of the U.S. National team; before the 1972 Olympics, he was replaced by International Falls native Mike Curran, who went on to a career in the World Hockey Association.

Newman also completed Air Force pilot training and was assigned to Norton Air Force Base in San Bernadino, Ca., where he flew C-141 transportation planes for the military. After more than six years of active duty, Newman joined United Airlines as a pilot, while remaining in the Air Force Reserve for 14 years.

He spent 35 years flying for United. “It was a very good job; exciting. You get to see the world from 35,000 feet. But the glamour went away after 9-11. That changed the whole atmosphere.” Newman was also furloughed for a couple of years in the early ‘80s, when the airlines encountered economic troubles. “But, as a career, I’d recommend it for anyone. Once you get up in the air, the pressure is off.”

Pursuing his pilot career, Newman lived in California for a few years, and put hockey on the shelf. But a United transfer to Chicago gave him the opportunity to resume his goalie “career,” playing with other United employees in a senior rec league. He also skated with a Northwest Airlines pilots team.

After moving to Minneapolis in 1991, Newman “hooked up with a bunch of guys from northern Minnesota” who recruited him to play goal for their Roseau-based senior team. That group has won eight championships in an annual USA Hockey over-60 tourney held each spring in Florida. He also stays active playing locally a couple times a week with an Air National Guard team, about nine months a year. He will play a few times during the summer “just so I remember how to put the equipment on.”

Speaking of equipment, that’s been the major change in Newman’s puck-stopping career. In his younger days, goalies wore smaller, heavier and more primitive versions of the gear that’s used today. “The catching gloves had no padding, the blockers were smaller and heavier, and the arm pads were like wearing a piece of carpeting.” In high-level competition, Newman’s arms and shoulders were a rainbow of multi-colored bruises. “All the old goalies were stand-up goalies, because they didn’t wear facemasks.”

Every goalie dreams about scoring goals. Newman had his best chance in an Air Force game. “In the late ‘60s and early ‘70s when teams started pulling their goalies (when trailing late in a game), the strategy was for the opposing goalie to move down to the offensive zone. One night, an Academy guy sent me the puck and I took a pretty good shot. But the other guy robbed me.”

Newman, who will turn 71 in March, isn’t sure how much longer he’ll play. “Going up and down so much is hard on the body. There aren’t many 70-year old goaltenders. I’ve had a good ride,” he says. But he’s not ready to Craigslist his goalie pads, yet.

He still loves the game but doesn’t take it (or himself) too seriously. He says the main reason he still keeps up with hockey is so he can play with his 7-year-old grandson. And most of us would agree—that’s the best reason of all.