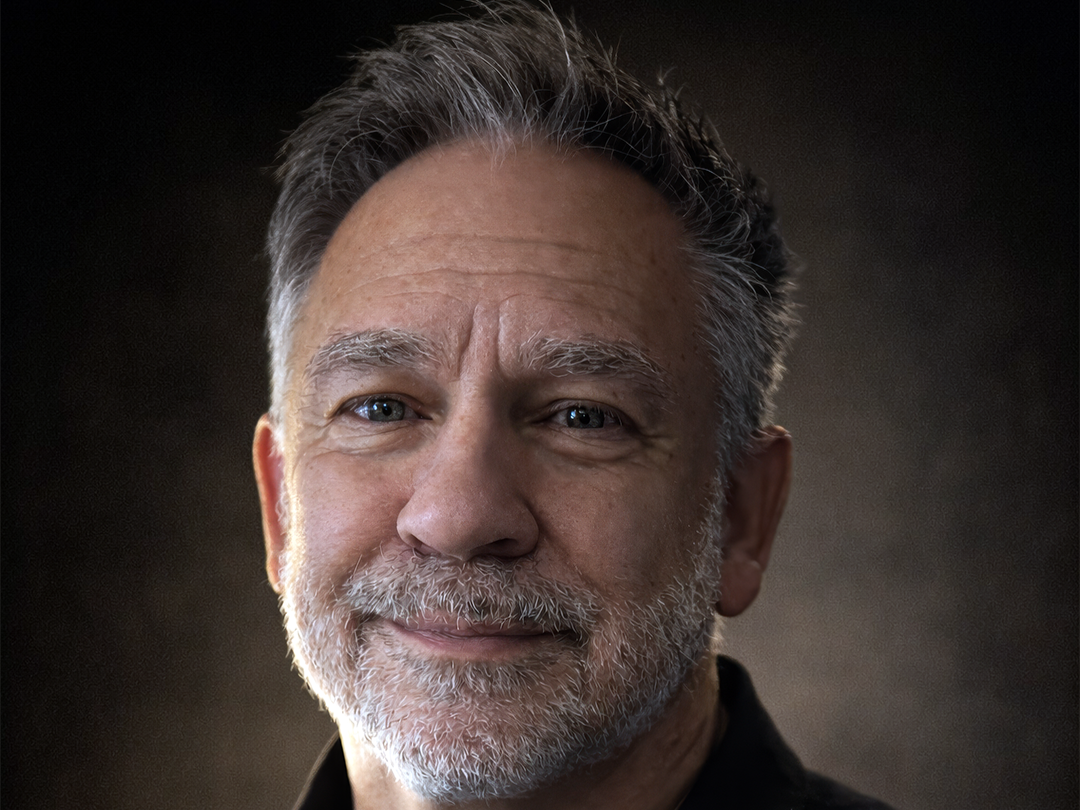

Margaret Sinnott-Wachholz. Photos: Chris Emeott

When you meet Margaret Sinnott-Wachholz, you’ll understand the Irish proverb, “Laughter is brightest where food is best.”

Meitheal—pronounced meh-hal—is an ancient Irish practice that demonstrates the way people come together to help one another, especially on the farm. It’s reflective of the hard-working, communal and familial nature of Woodbury’s Margaret Sinnott-Wachholz. She radiates this philosophy as if it’s the core of her inner being, whether in her work to renovate the historic Miller Barn at Valley Creek Park with the Woodbury Heritage Society or strengthening mental health outreach as a team member of Thrives at Woodbury Senior Living.

An Irish Upbringing

Wachholz’s ambition to share bygones seems to tumble out of her own history, growing up in the tiny village of Screen-Curracloe, County Wexford, located in the southeast corner of Ireland. “For me [preserving the past] is natural because we just live, drink and eat the whispers of our history in the pubs or in the elders’ homes. They’re always part of our gatherings with children, so that oral history is passed down,” she says.

Her most recent visit to the country she lovingly calls “the most important rock in the Atlantic Ocean” found Wachholz spending time with her 94-year old father, William Sinnott, and enjoying the taste of home. “Everybody calls dad Liam,” she says. “He’s always cooking. On a Saturday, he might have four to 16 people over for dinner; fresh fish, at least two vegetables and the potatoes with butter. Or they all go out for tea and scones on a Thursday afternoon. It takes time to do all of this, time to savor it. My brother [who is one of four siblings, plus a sister] comes down from County Mayo once a week to have tea with him.”

Her father, Wachholz says, and her Irish heritage, have taught her how to gracefully recognize difficult issues and rather than feel worried, how to enjoy the moments and remember to “… Do the best you can,” she says. “Our attitude is ‘Nothing surprises us but sugar.’”

She says, “My dad listens to the radio at 10:30 a.m. each day, with the elevenses, they call it, to hear the news but also the obituaries because we can’t forget.” (Elevenses is a short break for a cup of tea or coffee and sometimes biscuits, around 11 a.m.)

Radiating Joy

Wachholz’s joy is infectious and rivals only her determination. “I get teased a lot about how I even smile on the phone—nobody is watching from the other side. My husband on occasion has put on our voice mail: ‘You have reached happy, happy, happy,’ teasing me,” she says. “We may not be able to change the world, but we can help change the wee world around us.”

Part of this charm can be found in the work Wachholz does in Woodbury. She is on the boards of the Woodbury Community Foundation and the Woodbury Heritage Society, serves as chair of Woodbury Thrives—and you’ve probably seen her name in this magazine, as she serves on the Editorial Advisory Board for Woodbury Magazine. “I welcome everyone to the table,” she says. “My husband used to say to our children, ‘Make sure you’re doing the right thing.’”

Fellow Woodbury Irishman Roger Green can attest to her spitfire compassion. “Margaret is your quintessential Irish person: red hair, friendly, caring, polite, with a wonderful sense of humor, often teasing you,” Green says. “She’ll share tidbits of Irish wisdom, often starting by saying ‘We Irish …’ She has the ‘gift of the gab’ as the Irish would put it, loving to chat, especially about our community and the people who compose it.”

Before arriving in Woodbury, Wachholz met her husband, Rick, while working for McGettigan Group, a hotel consortium in Ireland. “I was running a restaurant at the hotel and met a gentleman from St. Paul, who had come to Ireland to work,” she says. Though she says she wasn’t impressed with his serving skills, she was enamored with his voice. “When you’re serving tea, it’s got to be with an English teaspoon, and he would serve it with the larger, French version. He was a Yankee,” she says, using her best “Yankee” accent. Rick had to return to Minnesota because his father was battling cancer, so the two began to write each other. “I saved enough money over the next year and a half to get myself over [to St. Paul] to rule out he wasn’t a crook, and we’re still married.” She recalls the $1.25 per call it cost to ring her parents back home, so, instead, she wrote to them of the beauty of fall that reminded her of home but also of the bitter winters. “I told them, ‘You couldn’t be stupid living here, or you’ll die in the cold.’” Shortly after her move in 1989, Rick joined the military, and they’ve lived in many countries since but have called Woodbury their home base since the early 1990s.

All three of their children, twins Niamh and Oison, whom she and Rick named after the Irish folk tale Tír na nÓg, and youngest Roan, have followed in Rick’s footsteps of a 28-year service in the Army; all three joined the National Guard. A humble pride covers her face as she talks about her family, and it’s evident she has raised them with her Irish, hard work ethic and values—the same ones that her and her five siblings.

As food continues to be central to her stories growing up in Ireland, she says, “You’re all taught to cook and be self-sufficient … There’s always something to do with potatoes; we don’t feel it’s a real meal unless it has potatoes.” Plus, she says she has a special place in her heart for Irish butter. “It has less water content and tastes so much nicer,” she says.

St. Patrick’s Day in the Homeland

St. Patrick’s Day in the Sinnott house was about Catholic Mass (St. Patrick is Ireland’s patron saint, who is celebrated with a holy day of obligation) and “maybe a pilgrimage to the graveyards and a holy well,” she says as her quiet Irish brogue begins to emerge. A holy well is a sacred site; a spring or water source thought to have mystical and healing powers or sources of luck. After walking to church and checking to make sure people had a shamrock, not a clover, on their lapel, Wachholz says it was common to spend time reading to each other, and it was also the time to plant new potatoes. For those who enjoyed the local pub, the walk after church meant a trip to empty the Pota Pádraig or Patrick’s Pot, liberally filled with alcohol. A lot of Patrick’s followers repeated this hallowed tradition several times until the pubs closed.

For many around the world, the Irish holiday is a day to celebrate with food. Common delicacies include boiled free-range pork shoulder, cabbage, parsnips, carrots and potatoes, lamb chops and Colcannon (a mixture of cooked and shredded cabbage and mashed potatoes). “We dislike being hungry,” she says with a smile and a reference to the history of Ireland’s potato famine.

A fellow Woodbury Irishman John Byrne agrees that food is at the center of St. Patrick’s Day traditions. “My mother was a chef in our hometown of Arklow, [County Wicklow in Ireland],” says Byrne, who has inherited her skills. “Every year on St. Patrick’s Day, we went to Mass, the parade and finished the day with a special dinner. We would have lamb boulangère or ham.” His suggestion for celebrating the holiday is to start a food tradition ode to your own family. Though green beer was not a tradition passed along from the old country, Byrne says after Shepherd’s Pie, he stops down to O’Malley’s Pub, making sure to head home by 8 p.m. Because, he says, “Nothing good happens after 8 p.m. on St. Patrick’s Day.”

Whether hops or Barry’s Tea (founded in Cork, Ireland, which is considered by many as Ireland’s culinary capital), Wachholz says sharing a bite to eat and something to drink is one of her favorite ways to pass along traditions to the Irish and the Irish at heart. To this end, Wachholz has shared recipes for some Irish sips and sups to help fellow residents get in on the St. Patrick’s Day spirit.