Photos: Tate Carlson

Woodbury’s June Fremont served during World War II.

June Fremont has seen and done a lot in her 98 years.

As one of the pioneering women to serve in the U.S. Marine Corps during World War II, Fremont chatted with Eleanor Roosevelt, met Harry Truman and marched with other servicewomen behind the casket during President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s funeral procession.

After the war, Fremont settled in Minnesota with her late husband, Leo (known as Lee), and raised six children with him in St. Paul. (A Duluth native who died in 1988, Lee was an Army tech sergeant during the war when they met stateside.) Over the years, she has welcomed 13 grandchildren and 31 great-grandchildren—with one more expected this month.

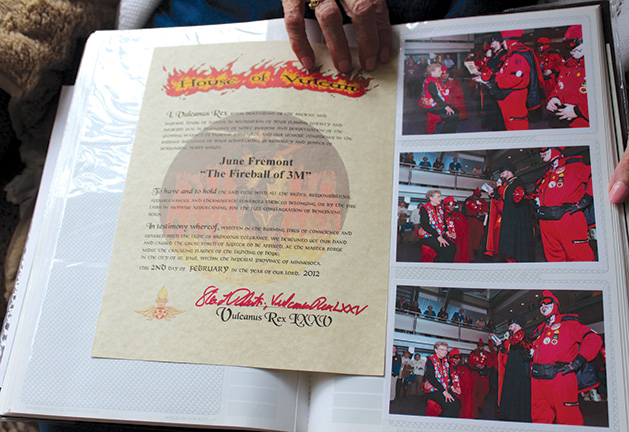

And, at age 50, with her last child in high school, Fremont embarked on a long career at 3M, spending most of that time working in the audiovisual department. She initially retired at age 73 but went back to work part-time until age 93.

Fremont, who lives in the Woodbury Senior Living villas, says she’s always tried to tackle every moment with a can-do attitude.

“I wasn’t afraid to try stuff,” she says. “If I failed, which I never did, so what? It’s not the end of the world.”

WWII Service

As she recollects back 70 years, Fremont’s meticulously archived scrapbook of her stint in the Marines—from 1943 to 1946—is cracked open. Page after page of photos and accompanying captions offer a glimpse into her past—from boot camp at Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune, N.C., to celebrating V-J Day while stationed in Hawaii.

“They don’t tell all,” says Fremont of the photos. “They just give a hint.”

Then known as June Schwark, Fremont enlisted in 1943, shortly after the Marine Corps authorized a Women’s Reserve. It was the last of the armed services to open its ranks to both genders during the war (there had been a Marine Women’s Reserve during World War I, in 1918).

Fremont and her fellow female Marines served in non-combat roles, mostly clerical positions, helping with the workforce demands of the two-front war. According to the National World War II Museum, about 23,000 women served in the Marine Corps Women’s Reserve.

“Everybody asks me if I was a nurse,” she says. “No, we weren’t nurses. We worked with the officers in recruiting, and doing that kind of stuff.”

Fremont says she saw it as her patriotic duty to join up after the December 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor by Japan. She chose the Marines because it was the “hardest to get in.”

“My father was in World War I,” says Fremont, who was living in her hometown of Chicago at the time she enlisted. “We used to hear his stories, and I was a true American—still am. That’s why I signed up to go in.”

After boot camp, Fremont worked in Washington, D.C., at the Pentagon. Her duties included sending out form letters from President Roosevelt to the families of Marines killed in action.

“I would try to add something personal to it,” she says. “I would talk to the boys bringing the casket because they usually were friends of the [fallen] soldier, and try to find out something he did as a hero or an anecdote, and add it to the letter. I thought it would be nicer for the parents to read something like that.”

It was while Fremont was at an event serving as an usher for Lord Halifax, the British ambassador to the U.S. at the time, that she met Eleanor Roosevelt.

“She asked me, ‘Where are you from? Are you getting enough to eat? Do you like the Marine Corps?’ We talked for about five minutes,” Fremont says. “So, I asked her, ‘How do you like being First Lady?’ And she said, ‘It’s tough.’”

When speaking to local students who are studying World War II, Fremont often jokingly mentions that she shook hands with Roosevelt. “I tell them I haven’t washed this hand in many years, so if you touch me, you’ve touched Eleanor Roosevelt,’” she says. “They come up and touch my arm all the time. It’s just a fun thing.”

In 1945, she was part of a contingent of Marine women to serve overseas in Hawaii, which didn’t become a state until 1959.

She says, “We went in and took over [the men’s jobs] so they could get home. I worked on the old, old, old IBM machines.”

When she and her fellow servicewomen arrived, four including Fremont were chosen to do publicity photos for recruiting posters and newspaper articles to send back home. Pictures in her scrapbook show her and the others posing in various tropical locales on Oahu, including testing out an outrigger on Waikiki Beach and donning hula skirts. In one photo, she jokingly holds a coconut up to her ear.

Fremont says she and her fellow Marines celebrated V-J Day three times before it was official. “We’d hear from officers that peace was declared, and would start packing, washing, ironing and get ready to leave and oops … false alarm!” she wrote in her scrapbook.

In 1946 all Marine Corps Women’s Reserve units were disbanded and most women—including Fremont—returned to civilian life.

Fremont downplays the role she played in helping blaze a trail for women in the Marines. Congress passed the Women’s Armed Services Integration Act in 1948, allowing women to serve as a permanent part of the regular armed forces, including the Marines. Today, according to the Women Marines Association, females constitute about eight percent of the Corps.

Her son, Daniel, who also lives in Woodbury, says whatever the moment demanded of his mother—at work, raising kids, or in the service—she rose to the occasion.

“That’s how I view life, based on how she views life,” he says. “You live the moment, and you participate, and it’s not bigger than you, and it doesn’t need you. That moment will go on whether you exist or don’t exist. We see things outside of us as bigger. We’re just a part of it, and we get the privilege to participate.”

Still Active

All these years later, Fremont says the Marine Corps holds a special place in her heart.

“I did a lot of things in the service, and I’m still doing things with it,” she says. “It’s just instilled in me.”

Fremont served as the oldest Marine at the 242nd Marine Ball in 2017, one of the first women to do so. Each year, the Marine Corps celebrates its birthday by having the oldest and youngest Marine represented. (The honor is ceremonial; there are still a few Marines older than her.)

“They bring this huge cake out, and they cut it and give you plate with two forks,” she says. “I take a bit of the cake and pass it on to the youngest Marine. The tradition is I am passing on my knowledge.”

She also took an Honor Flight in 2014. Through the program, veterans are flown to Washington to visit the memorials built in recognition of their service.

By chance, the night she returned home, there was a group of Marines at the Minneapolis-St. Paul Airport, on their way to Afghanistan.

“I tell you the Lord must have made those arrangements,” she says. “I got three or four Marines together, and we would pray for them. And then I would say, ‘Now be sure to write your mother. Don’t smoke and don’t drink and be good.’”

Fremont stays active, regularly playing cards, and enjoying visits from her family. A photo with most of her extended family hangs in the living room of her apartment.

She also served as grand marshal of Woodbury Days in August, aptly riding in a Jeep during the Grande Parade. One of her duties while serving in Hawaii was driving her commandant around in a Jeep.

“I’ve been blessed in more ways than you can think of,” she says. “I’ve had a wonderful life, and it all started with my mother and my father. They were great people. If I go tomorrow, I’m ready. I’m ready to go to a better place.”

For more information:

womenmarines.org

nationalww2museum.org

marineparents.com

womensmemorial.org